Frontline Blog

Congress Took 233 Days To Respond. Here’s How To Prepare For The Next Zika

October 2016

By Barbara Ferrer

Dr. Ferrer is a member of the Coalition’s Alumni Council, as the Former Director of the Boston Public Health Commission. This blog originally appeared on HealthAffairs.com.

Congress recently passed federal funding for the nation’s response to the Zika virus, and the manner in which they provided those funds exposed a serious flaw in the way our nation handles disease outbreaks. In the time between the White House’s initial request for funding in February and the passage of the bill in September, the outbreak escalated dramatically, nearly unchecked by federal lawmakers. The entire process took a grand total of 233 days, which is simply far too long. It did not need to be this way.

FAILURE TO ACT

Over the spring and summer, the Zika virus infected more than 3,300 Americans in the states and almost 20,000 in the U.S. territories. While members of Congress effectively sat on their hands, in addition to ongoing transmission from international travel, thousands of pregnant women were infected with the Zika virus in Puerto Rico, and Miami residents were infected in their own backyards. Babies are now tragically being born with microcephaly, a birth defect that often damages a child’s brain in such a way that it creates lifelong debilitation.

As the number of infected Americans mounted and the pregnancies at risk continued to grow over nine long months, Congress still did not act. In fact, the federal government effectively cut local health department budgets by nearly 7 percent in the midst of this crisis. This approach is emblematic of Washington’s record of significantly underfunding America’s public health system. For example, funding for public health preparedness has shrunk by more than 30 percent over the last decade and hospital preparedness funds have been slashed by more than half. Dismantling critical infrastructure does not put us in a strong position to effectively fight major outbreaks like Zika, and we will continue to be at risk until state and local health departments are routinely funded.

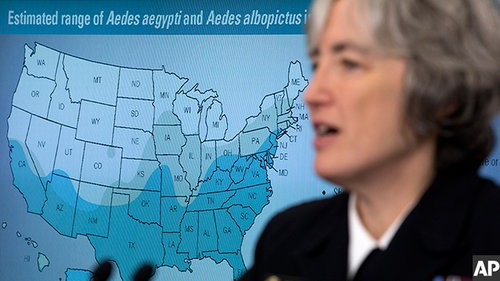

Quite simply, we need a way to enable quicker responses to acute disease outbreaks. Due to modern travel patterns and climate change, these viruses can find a way to jump borders and oceans with greater speed than in the past. If we are not under siege in the coming months from a known foe like pandemic flu, we should expect to be hit again soon by an emerging disease, like Zika or Ebola. Relying on a legislative body that takes months to respond is not an effective plan.

A BETTER FUNDING MECHANISM FOR RAPID RESPONSE

Members of Congress finally addressed Zika, but now they must prepare the nation for the next emergency. We could save countless lives if instead of letting each new infectious outbreak turn into a political football, we created a sound funding stream for public health that can be activated swiftly and appropriately by the executive branch, instead of a vast legislative body like Congress. This solution actually already exists, and it is an essential tool that Washington has nearly forgotten: the Public Health Emergency Fund.

This fund could give state and local health departments a crucial running start when an outbreak hits. The problem is that it’s almost empty, with a measly $57,000 remaining, and there are no concrete plans to replenish it. None of the $1.1 billion Congress set aside for Zika will be directed to restoring it, and there is no annual appropriation for this fund either.

If this fund is financed appropriately and is readily accessible to critical health decision makers in the executive branch, we would be better able to respond to public health disasters that demand quick action, without partisan politics getting in the way. Right now, using money from the fund requires Congressional action, but this authority should actually be in the hands of the executive branch, which has shown itself to be far more nimble in emergency situations, from hurricanes to terrorist attacks.

Similar to the sequence of events that occurs when a natural disaster, like a flood or tornado, strikes, a public health emergency fund would allow an immediate distribution of funds, just like the Federal Emergency Management Agency taps into an existing pot of money. In the case of a disease outbreak, a similar declaration would need to be made, and the executive branch could allocate money from the fund. We can all agree on a fiscally responsible and accountable way to restore the fund by placing appropriate restraints on these dollars so they can only be used for true public health emergencies.

No matter how prepared health departments are for different scenarios, accessing emergency funding will always be essential. Health departments routinely train to respond to any number of disasters before they strike. But each outbreak presents unique, and sometimes unforeseen challenges, creating the need for a specific response that triggers emergency funding. For instance, only months ago, scientists had not yet confirmed Zika’s connection to microcephaly, so many of the precautions taken to track and protect expectant mothers exposed to the virus were not yet in place. Although it could not be predicted, that response was essential, and took significant resources to get right.

State and local health departments have responded, remaining resilient, despite the absence of emergency funding from the federal government. It’s time for Washington to design an emergency response system for disease outbreaks that is just as strong as its response to weather emergencies or terrorist attacks. Our country will not be truly prepared until we take the politics out of emergency response and give experts access to the tools they need to get the job done, as soon as they need them.