Promoting and protecting the public’s health: recommendations for a new Administration and Congress, 2025

October 2024

The Big Cities Health Coalition (BCHC), representing the leaders of health departments serving nearly 61 million Americans, calls on the incoming Administration and Congress to enhance support for local public health systems.

2025 Transition Paper

Download the full brief 2025 Transition PaperExecutive summary

Public health extends beyond clinical care, encompassing factors like prevention, safe housing, full employment, and environmental conditions that promote community well-being.

Urban health departments play a critical role in responding to major health threats while also managing ongoing functions such as vaccinations and chronic disease prevention. To bolster these efforts, BCHC urges the federal government to provide sustained funding, flexible resource allocation, and direct support to local health agencies, ensuring preparedness for future public health emergencies.

Key recommendations include reauthorizing the Pandemic and All-hazards Preparedness Act (PAHPA), establishing an Adult Vaccine Program, and prioritizing health equity in all policy decisions. Additionally, we advocate for stronger public health data systems, workforce development, and collaboration across government levels.

To promote effective leadership, BCHC recommends appointing experts with local or state health experience to federal positions. A resilient, well-funded, and equitable public health infrastructure is essential to addressing health disparities and improving overall health outcomes for urban populations nationwide.

Specific policy and funding recommendations

Get more details about what big city health departments need to protect and promote their communities’ health.

Introduction

Public health is the science of protecting and improving the health of people and their communities by promoting healthy lifestyles, researching disease and injury prevention, and detecting and responding to infectious diseases.

Overall, our field works to protect the health of entire populations. Health is not just health care. Studies show clinical care only accounts for about 20 percent of one’s health status while our social and environmental conditions have the greatest impact on our potential for health and wellbeing.

To create the conditions for healthy vibrant communities, we need full employment and a livable wage; safe, affordable housing; access to healthy food; well-functioning public transportation; safe, appropriate K–12 education; and access to routine and preventive health services. A truly healthy city requires a fuller commitment to health, defined broadly.

Studies show clinical care only accounts for about 20 percent of one’s health status while our social and environmental conditions have the greatest impact on our potential for health and wellbeing.

Our members are on the front lines of public health in urban America, working every day to make it easier for people to achieve optimal health and safety. Big city health departments address a wide range of everyday threats, including chronic and infectious disease, environmental hazards, and substance use disorder. They focus on prevention, lay the groundwork for healthy choices that keep people from getting sick or injured, put policies in place to create healthier communities, and convene key stakeholders who are both supporters and skeptics of their work.

Big city health leaders work with their communities to build resilience, remove barriers to health equity, respond when public health emergencies occur, and lend support throughout the recovery process.

Importantly, non-governmental entities also play a critical role in getting and keeping communities healthy and safe. In previous work , we have called this a “public health ecosystem approach,” which recognizes and incorporates the essential roles and leadership of all the contributors in the system. From public health departments and other government agencies to non-governmental organizations; from community-based organizations and community residents to organizers and advocates, all are needed and valued.

While this document will focus primarily on what a new Administration and Congress should do to protect and promote the public’s health, we want to highlight that government can’t do this alone.

Advancing BCHC’s Urban Health Agenda: building more equitable communities

Large urban areas uniquely bring together density and diversity. They are home to large employers, health systems, academic institutions, and cultural destinations, as well as transportation hubs. As such, big cities are often drivers of local, regional, and even national economies.

Just as density and diversity provide opportunities to bolster health and quality of life among large swaths of people, the consequences of generations of structural inequities also make urban areas vulnerable to extreme disparities in resources, opportunities, and health outcomes.

These disparities, if not addressed urgently and systematically, threaten to undermine the immense value of our nation’s cities. For instance, people in one neighborhood can expect to live 20–30 years longer than their neighbors who live just a few miles away, a disparity that can be traced back to systemic disinvestment of resources or through racist policies like redlining.

This significant gap in life expectancy— particularly pronounced between Black and white communities—is magnified in cities, as we saw to devastating effect during the COVID pandemic. Importantly, racial and ethnic inequities and disparities ultimately undermine the health of everyone.

It is often said that a community is only as healthy as the least healthy within, which has been illustrated time and again during a host of health crises. At the same time, we can also see positive examples of this: Angela Glover Blackwell refers to the “curb cut effect,” which highlights how investing in one group (in this scenario, those in wheelchairs) affects the broader well-being of a community (making sidewalks more accessible for those pushing strollers, for example).

Investing in our governmental public health ecosystem will enable our nation’s health departments to extend that curb cut effect to all aspects of our health and well-being.

The role of governmental public health departments in America’s cities

Our public health system is a patchwork quilt of first responders, practitioners, and local, state, and federal experts who work to keep our communities healthy and safe. All levels of government have a critical role to play in this system.

Governmental public health includes the health departments that work to promote the health and safety of their communities at the state, territorial, county, and city levels. These departments have primary responsibility for protecting local, state, and territorial jurisdictions under our federalist system. There are more than 3,000 local health departments that work in tandem with the 59 state and territorial health departments, as well as Tribal departments. All collaborate with federal health leadership, particularly the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

SOURCE: https://www.naccho.org/about

BCHC members—more than 30 of the nation’s largest urban local health departments—are key players in building a healthier, safer, and more secure nation. Metropolitan areas are home to 80% of Americans, and BCHC member health departments serve nearly 61 million or one in five Americans. At their best, these health departments positively affect entire populations and create an environment in which the healthy, safe option is the default option.

The COVID-19 pandemic made clear how important governmental agencies are in protecting and promoting the public’s health from infectious disease outbreaks or similar emergencies. But health departments do much more than respond to catastrophic events; they also ensure our food and water are safe, regulate tobacco, reduce the harms that can come from substance misuse or extreme heat, provide vaccinations for dozens of communicable diseases, and much more.

Our elected leaders and their appointees make policy choices every day that affect the health and well-being of our communities. These choices can either promote safe and healthy environments or unsafe, harmful ones; ensure access to resources for health for all or just for a privileged few; and inspire with creative design or perpetuate historical oppression and marginalization.

Policy action and innovation at the local level does not just change the trajectory of health for the populations that city health leaders directly serve—they also drive national change. In the last decade, the significance of local governance has only grown as federal-level policymaking has stagnated. At the same time, in many states, we are seeing unprecedented rollbacks of local authority .

The tripartite governmental public health system—federal, state/territorial, and local—is essential to ensuring the health and safety of communities. Relationships can be supported and strengthened through transparent communication and consultation, data sharing across all levels, and robust, predictable funding. Effective public health practice depends on action at the federal, state, tribal, local, and territorial (STLT) levels of government.

Public health has always dealt with difficult or “political” issues, from HIV to safer drug use to access to appropriate family planning. That said, the COVID response in 2020 and 2021 became increasingly divisive and partisan , which not only put people’s lives at risk, but also damaged the field’s reputation.

To do its work well, the public health workforce should be protected from undue partisan political influence.

Elected officials at all levels of government need to rely on experts that have spent their entire careers planning for and responding to public health emergencies. Health officials must be relied upon to explain whether and how the science has changed and own when mistakes are made.

Data and science must be balanced with the reality of what is occurring in our communities. While we must lead with science, it must be validated by what is being seen in the field by practitioners.

The federal role

In our diffuse and complex governmental public health system, the federal government provides funding; command and control in times of crisis; policy guidance and research; and facilitates data collection and access. The federal government is also meant to support STLT governmental public health activities across the board. At its best the federal government can facilitate positive policy change to protect and improve the public’s health.

Command and control

In times of true emergency, the federal government plays an important command and control role, and must lead and provide resources for a comprehensive detection and response infrastructure, developed and carried out in tandem with local and state governments. This works properly only if states and locals are seen as true partners, providing situational awareness of what is happening on-the-ground and to inform what is needed for the response.

To support this critical command and control need, Congress established the White House Office of Pandemic Preparedness and Response Policy (OPPR) in 2023 to coordinate the federal agencies’ domestic response to public health threats that have pandemic potential or that may cause significant disruption. Their ongoing work includes addressing potential public health outbreaks and threats from COVID-19, measles, mpox, polio, avian and human influenza, and RSV.

One immediate way that Congress can support federal, state, and local coordination, would be to reauthorize the Pandemic and All Hazards Preparedness Act (PAHPA), a step that is long overdue and critical to supporting the nation’s ability to prevent and respond to the next pandemic. In conjunction with this reauthorization, we also urge Congress to create an Adult Vaccine Program, which would provide vaccines to adults who are un- or under-insured similar to the Vaccines for Children program that currently exists. It is well documented that federally-funded, no-cost vaccines led to increased uptake during the height of the COVID pandemic. The short-lived Bridge program provided more than 1.5 million free COVID vaccines . The program ended in 2024, a casualty of funding rescissions by Congress.

CDC sits at the center of our governmental public health system, which works to promote health and prevent harms from emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases, human-made and natural disasters, and non-infectious disease and injury.

In addition to its ongoing COVID-19 response, over the past two years, CDC has monitored and investigated outbreaks of mpox, measles, and polio domestically and around the world, and continues to build the nation’s pandemic flu preparedness, as highly pathogenic avian flu outbreaks in birds and cattle have grown.

Effective research, data, and implementation of programs require significant connection and collaboration with local and state public health partners. Through cooperative agreements and grants, CDC provides funding to all states and territories and a growing number of local health departments and tribes. This enables close collaboration to track data, connect systems, and implement effective community-level actions. It also sometimes allows STLTs to hire personnel (like epidemiologists) to identify concerns and create evidence-based interventions to prevent death and disease.

While the public largely associates CDC with infectious disease response, its work to respond to other health threats is equally important. For example, public health approaches led by CDC have also been critical to understanding the extent of the opioid crisis. The same approaches that CDC uses to detect and respond to infectious disease—monitoring, early identification, and connecting research to action—are needed to respond to the over 100,000 deaths annually from drug overdoses. The spread of infectious disease among intravenous drug users is an issue that relies on expertise from both infectious and non-infectious centers at CDC—working together across silos. Overdose and suicide are both among the leading causes of death and major drivers of health care costs. CDC’s Injury Center uses data to understand the scope of the problem and develop necessary interventions. Importantly, these responses are community-based and preventative in nature.

As the COVID-19 pandemic showed, chronic disease and infectious disease are inextricably linked. Indeed, in the absence of vaccines, good underlying health is the best way to prevent severe infection and death from communicable diseases. The world is continuing to experience greater linkages between infectious and chronic diseases, where individuals with a chronic illness are more susceptible to its effects and leaving many patients living with the chronic condition of long COVID. Therefore, any efforts to improve pandemic preparedness and prevent the spread of infectious disease must also include efforts to prevent chronic disease, address health disparities, and ultimately, improve resilience, health and wellness for all.

Funding, leadership, policy, and research

Federal funding accounts for a large percentage of STLT health activities across the country; in fact, more than 80 percent of CDC’s domestic budget goes to states and localities across the country each year.

The nation’s leading health agencies—like all of those across the Executive Branch—need to be led and staffed by experts in their field. These appointees should go through a rigorous, thorough and expeditious confirmation process that leads to positions based on professional qualifications and relevant experience. In 2025, a new Administration will appoint more than a dozen leaders to various HHS agencies, including the CDC Director. BCHC strongly recommends that the nominee for this position have governmental public health leadership experience at the local or state level.

Policies related to health care access, health insurance coverage and affordability, paid sick leave, universal basic income, childcare, and housing would go a long way to creating the conditions for health and equity for all Americans. The federal government can implement these policies at a national level and/or support state and local versions of these policies through various policy levers. Local health departments actively advocate for and are ready to operationalize these upstream, population-level interventions to improve health and decrease inequities. The federal government can also support local policy levers by making recommendations and using purse strings to promote implementation.

BCHC strongly recommends that the nominee for this position [CDC director] have governmental public health leadership experience at the local or state level.

An equity approach to federal health policy and funding decisions should be data driven and designed for targeted and universal impact. Importantly, a health equity approach involves systematic assessment of how different groups might be affected by policy and funding decisions to identify potential adverse consequences and maximize benefits to health, well-being, and longevity.

To identify gaps in our current understanding about what works to promote health and prevent disease and injury, there should be an explicit commitment at the federal level to include more Black, Indigenous, Hispanic, and other underrepresented groups in research studies. In addition, federal resources should ensure data and resources generated by federally funded research are shared at all levels of governmental public health.

Administrative law, i.e., regulatory and rulemaking processes, is a critical part of policy making. For 40 years, agencies followed the so-called Chevron Doctrine, which generally guided courts to “defer to” agency processes. In many instances, Chevron deference proved valuable in allowing federal agencies to make determinations about complex, technical issues, rather than placing that decision with judges less familiar with the subject matter.

In the summer of 2024, however, the Supreme Court, in its Loper Bright ruling, found that Chevron Doctrine was inconsistent with our nation’s separation of powers, finding that it is the courts that should be interpreting Congressional intent, not the agencies . While it will take time to assess the full impact of this decision, moving forward Congress needs to draft legislation with clearer intent and be explicit where they affirmatively mean for agencies to engage in rulemaking.

That said, for those agencies that rely on rulemaking to put policy into place, the Loper Bright ruling could result in regulations winding up in court, bringing regulatory and policy making processes to a standstill. Further, federal health agencies could become more cautious, diverting more resources to preparing for an onslaught of lawsuits. Federal agencies and Congress must work together to implement policies that improve the health and wellbeing of communities.

The state and local role

State and local health departments must also work closely together. States have substantial authority over public health , which is supported in part by the 10th Amendment of the Constitution. Some public health authorities are also delegated to or carried out by local jurisdictions; such allocation of authority varies immensely from state to state.

That said, almost all local health departments, including those in BCHC, depend on their states for funding, including to receive federal pass-through dollars. Others depend on states for access to public health labs and other resources, such as vaccines. By and large, however, many BCHC health departments are as sophisticated and resourced as their state counterparts. Importantly, local health officials are trusted leaders and partners in their community.

Public health infrastructure

Public health systems in the United States are built on an infrastructure of workforce, information systems, and organizational capacity. As with any organization, governmental public health departments can’t do their work without the appropriate staffing, systems, and supplies. This infrastructure, which has been poorly supported for decades despite significant emergency dollars during the height of COVID, is the foundation for planning, delivering, evaluation, and improving the health of those living in communities across the country.

The system as a whole is far more efficient when we have systems and people in place in times of calm that can surge in emergencies. Building a plane as we fly it, which was done during the pandemic as it relates to data systems, for example, is neither necessary nor responsible. Sustained support for workforce and data is what builds a strong infrastructure no matter the routine or emergent public health challenge.

Funding

First and foremost, federal policymakers must sufficiently and reliably fund all levels of the public health system. For the most part, public health funding flows from the federal government to states and then, eventually, to local communities. Even with a combination of funding streams the local public health system is persistently underfunded through this incomplete and disjointed funding process. Our communities need a well-resourced public health system to prevent and respond to public health emergencies and address everyday health issues. When a house is burning, you can’t go out and buy a fire truck—it’s already too late. Funding the public health system is no different. While other emergency response agencies are recognized as critical, governmental public health is chronically underfunde d and often forced to do more with less . Federal policymakers must sufficiently and reliably fund all levels of the public health system.

Further, the way we fund public health is all too often siloed by program or disease, so that little funding goes to support the underlying infrastructure, such as epidemiology and surveillance systems; workforce; and health and risk communication. Funding must be flexible as health threats continually change. Public health needs to take an “all hazards” approach and be nimble in addressing health challenges, which is often hindered by restrictive funding streams. CDC has in recent years worked to address this by encouraging innovation and leveraging dollars as is permissible by Congressional appropriations. Congress should enable CDC to continue this practice.

When a house is burning, you can’t go out and buy a fire truck—it’s already too late. Funding the public health system is no different.

At the same time, because funds are passed from one level of government to another, accountability is difficult, and the process is incredibly time-consuming and often inefficient.

Funds must be sufficient and flexible to ensure they are used as effectively and efficiently as possible, and in some cases, that means sending dollars directly to the local level. When direct funding is not available, states should receive specific instruction to grant local communities an appropriate portion of the funds in a timely manner without additional requirements beyond the federal guidelines. In the past, even when federal funding has been allocated for local response, states have often been slow to deliver these funds to local health departments. This delay can significantly affect local departments’ ability to hire and train needed staff, as well as ramp up programs. Local leaders, not just states, should be able to directly request resources and staffing from federal agencies and partners when needed.

CDC should continue to broaden its direct grantmaking pool to include, at a minimum, the 107 jurisdictions recently funded under the Public Health Infrastructure and Grant Program (PHIG). This universe of grantees includes the 50 states and Washington, D.C.; eight territories/freely associated states; and 48 local health departments that either serve cities with a population of at least 400,000 or counties with a population of at least 2,000,000 based on the most recent U.S. Census numbers.

As of January 2024, CDC has awarded $4.35 billion to strengthen public health infrastructure across the nation. These funds help ensure that 107 state, territorial, and local health departments have the people, services, and systems they need to promote and protect health in their communities

These funds expire in November 2027, so health departments face another funding cliff. Therefore, Congress should continue to provide funding through the public health infrastructure line in CDC’s budget. The dollars can continue building a stronger, public health system ready to face future health threats and ongoing challenges.

Part of what makes these federal awards unprecedented is that they have been delivered directly to 49 local health jurisdictions (including D.C.) and are flexible in nature.

CDC has further made a concerted effort to expand funding opportunities to large city and county health departments through Overdose Data to Action: LOCAL, which funds 17 BCHC jurisdictions and an additional 23 local health departments, and the National Initiative to Address COVID-19 Health Disparities Among Populations at High-Risk and Underserved, Including Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations and Rural Communities grant, which supported 108 jurisdictions (states/territories/locals) to implement an equitable response during the COVID pandemic.

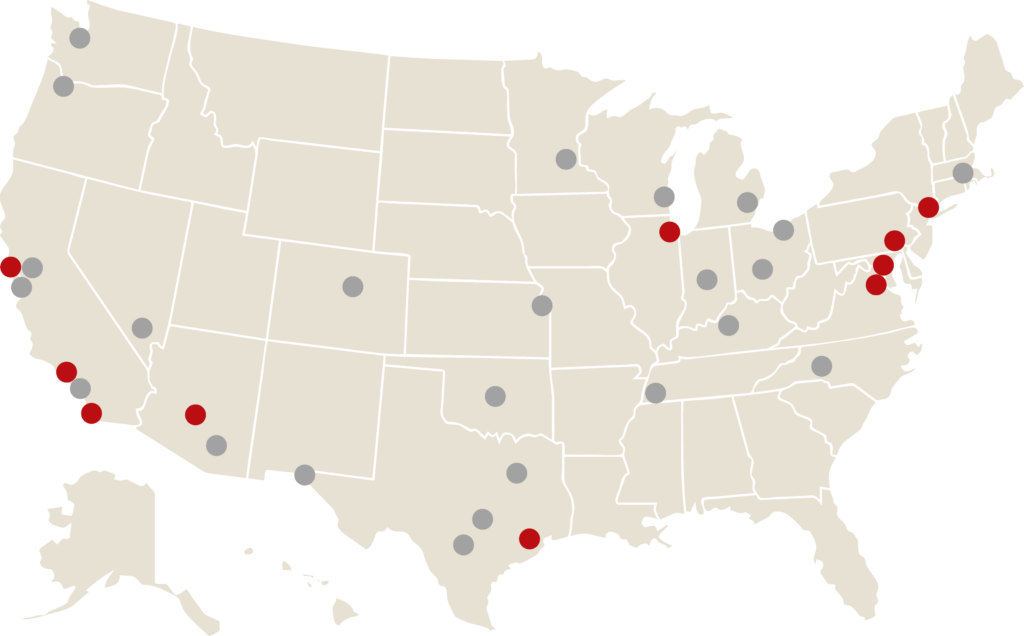

This is in stark contrast to some of CDC’s traditional, disease-specific funding which has gone to only a handful of the nation’s largest jurisdictions (as shown on the map below). BCHC encourages CDC to continue to seek opportunities for direct funding to the local level, particularly among the nation’s largest local health departments.

Map – Some large local health departments receive programmatic funding directly from CDC. Most local health departments don’t.*

*Jurisdictions marked in red—that is, 10 of America’s largest cities receive direct programmatic funding for certain activities. These data are as of October 1, 2024, and are subject to change in future years. Funded cities are: Baltimore, Chicago, Houston, Los Angeles, New York, Philadelphia, Phoenix (Maricopa County), San Diego, San Francisco, and Washington, DC.

The Prevention and Public Health Fund (PPHF) was created as part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and is one of the few mandatory funding streams that was meant to support prevention and public health activities—i.e., those activities that happen outside of a doctor’s office that affect the health of the whole community. It was meant to complement insurance coverage recognizing that access to clinical care is necessary but is not sufficient for getting and keeping our communities healthy.

Even with changes to the original intent of the PPHF these dollars are essential to local and state health departments to carry out their missions. But the PPHF has been under threat practically since its inception. Due to federal budget constraints, PPHF funding has supplanted base CDC funding rather than supplementing it. Further, annual increases to the PPHF have been eliminated multiple times to use as a pay for other non-CDC related programs. In FY23, it accounted for 9.7 percent of CDC’s budget .

Over the years, the PPHF has supported a number of programs aimed at addressing the leading causes of death—chronic diseases like diabetes, stroke, and asthma—and the immunization program, which plays a critical role in ensuring that lifesaving vaccines get to those most in need. At a minimum, the PPHF must be protected and fully funded.

Workforce

At the core of governmental public health is its workforce, which has been shrinking for years and is constantly being asked to do more with less. The workforce was in crisis before the pandemic, with local health departments losing over 20 percent of their workforce compared to before the 2008 recession. Over the same period, the nation’s population increased by 8 percent . In 2019, the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) governmental public health staff dropped from 5.2 per 10,000 people to 4.1 per 10,000 people. The 2022 local governmental public health workforce was about 163,000 FTEs, and the overall size of this workforce remains largely unchanged since 2008 . By 2025, more than half of the state and local governmental public health workforce is expected to leave or retire —a potential loss of 129,000 workers, including 24,000 from big city health departments.

The Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey (PH WINS) has repeatedly found challenges with recruitment and retention and an impending brain drain, due to an aging workforce. Retention issues in BCHC member health departments suggest professional development and opportunities for advancement affect this, as well as challenges with hiring the “right” staff into the right positions.

We need to invest in a long-term, well-funded, well-trained, and diverse health workforce that reflects the community and is employed by, or detailed long term to, local health departments. Sustained, predictable federal funding will enable them to create and sustain jobs that support core public health functions, work across health department programs (instead of being tied exclusively to siloed, disease-specific programs), and support foundational capabilities (including assessment, surveillance, and access and linkage to health care). In this way, all Americans will be able to benefit from these efforts no matter where they live.

Data at a local level

Data powers public health decision making, but our nation’s health data systems are woefully outdated. It is well documented that prior to 2020, the governmental public health system’s data infrastructure was lacking in most jurisdictions . The effectiveness of the nation’s public health data system relies on efficient and accurate data flow from origin point to STLT agencies to the federal government. While data at the federal level are essential, it is important to emphasize that individual-level data are often collected at the STLT level where immediate public health response happens. STLT health departments have the legal responsibility and authority to protect people living within their jurisdictions; they need timely data to respond immediately, efficiently, and effectively “on the ground” and to use an equity approach to the response. Investment in system modernization at the STLT level is essential to support this multidirectional flow of public health data and ensure the rapid delivery of health care data to public health.

At a 30,000 foot level, data modernization to transform the nation’s public health data systems requires interoperability–ensuring all five of these core data pillar systems can receive, communicate, and share data effectively with one another; an enterprise-wide approach that remains disease agnostic; data standards to ensure data can be shared across systems, between jurisdictions, and with the federal government; security to protect privacy; a workforce that is trained in appropriate data science technology; and partnership with the public and private sectors to build, maintain, and refine the public health data superhighway and establish leading-edge public health data systems and processes.

During the pandemic, the public health emergency declaration facilitated coordination between federal, state, and local agencies to share critical public health data used to prepare for and respond to public health emergencies. This allowed for faster data flow at all levels including from health sector partners. In the absence of the flexibilities provided to CDC, the agency must put in place more than 60 different data sharing agreements for any new reportable disease. This takes valuable time that could be otherwise devoted to responding to a new outbreak. Congress has considered legislation to permanently give CDC so-called “data authority” to effectively collect and coordinate data. BCHC supports expanded data authority for CDC would allow for more complete and timely data sharing to support decisions at the federal, state, and local levels, while also reducing burden on providers. Likewise, such legislation could create standards to improve and secure the transfer of electronic health information and establishes an Advisory Committee to ensure that public health data reporting processes are carried out effectively .

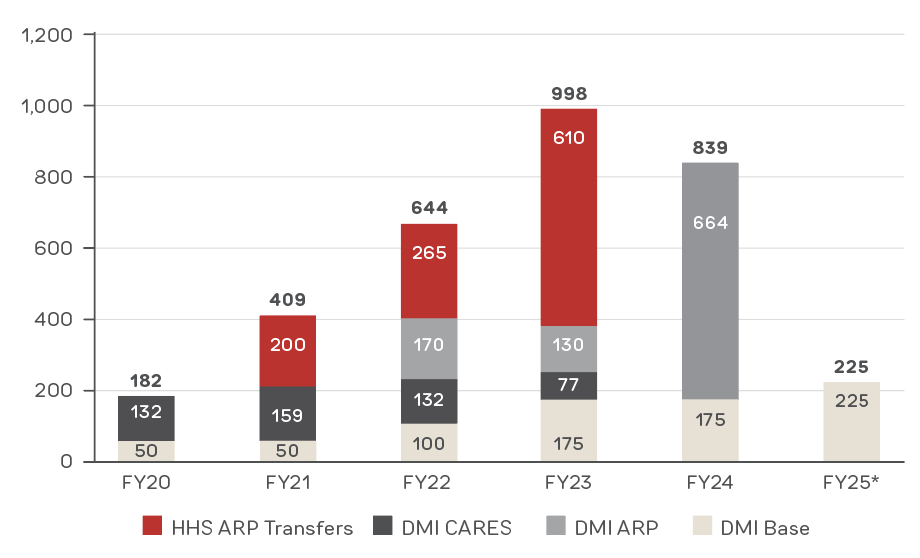

Graph – CDC data modernization investments over time

(Obligations by fiscal year, categorized by funding source; all amounts in millions USD)

* Projection based on the FY25 President’s Budget. Source: A presentation at “The Power of State Leadership: Improving Public Health Data for Economic Growth,” August 27, 2024

Congress must provide predictable and sustained federal funding to build upon historic investments and progress made during the pandemic. The graph above shows the $4.1 billion that has been appropriated from FY20 to FY24. While this has been a critical influx of dollars for public health data infrastructure, there are two key challenges moving forward. First, the vast majority of the investment has been with emergency dollars and both CDC and its state and local partners face a very real funding cliff. Second, the vast majority of dollars have gone to states, with varying degrees of resources going to local jurisdictions. CDC estimates $1.1 billion has gone directly to STLTs, while an additional $426 million has gone to indirect support and technical assistance to STLTs.

BCHC and its partners in the Data: Elemental to Health campaign, support a robust and sustained federal investment in public health data modernization at CDC and for STLT health departments. Investing in data modernization, which the campaign partners estimate will cost $7.84 billion at the STLT levels in five core pillars (see above) over five years, is the key to improving our public health data infrastructure. Without sustained funding, neither STLT public health authorities nor CDC will be able to implement, maintain and update the federal data assets necessary to achieve timely public health data to inform public health action and save the lives of babies, children, and adults in this country.

2025 Transition Paper

Download the full brief 2025 Transition PaperAcknowledgments

We thank our board members and partners who took the time to review this document.

We are grateful to our funding partners for their ongoing programmatic support of BCHC. Opinions in this report are the Coalition’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of any one member or funder.