Urban Health Agenda outlines vision for public health

June 2022

Building Healthier, More Equitable Communities

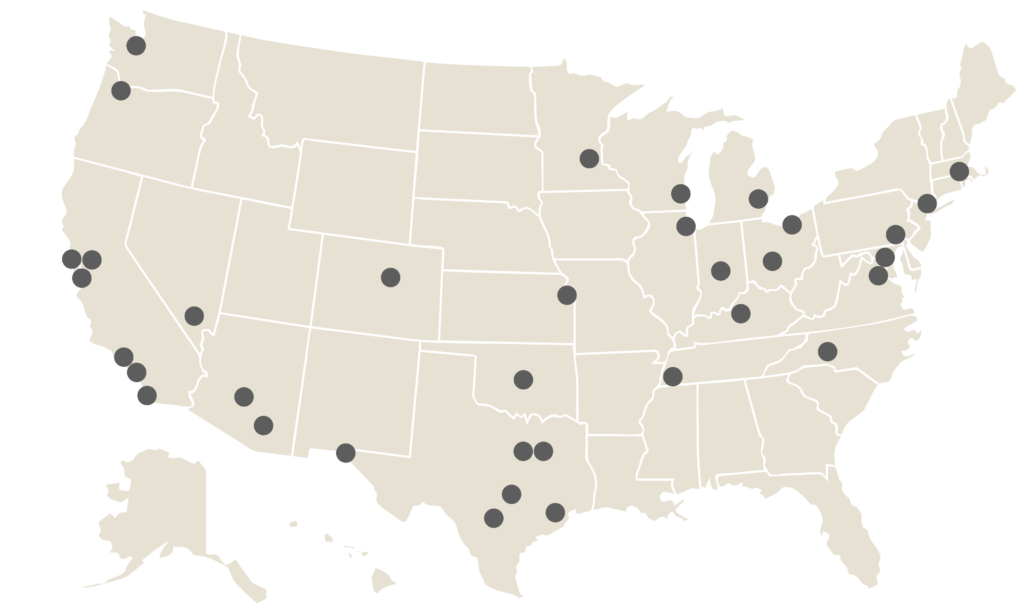

The Big Cities Health Coalition (BCHC)—a coalition of 35 of the largest health departments in the United States, serving more than 61 million people—seeks to advance a shared, actionable vision to transform urban health.

In this vision, all government agencies and relevant community-based organizations work together to promote health and safety, in part through dismantling structural inequities and systems built on generations of racism.

This vision rests on two pillars: that health is more than health care and that the well-being of urban populations centers on a broader definition of “health.”

Read on to learn what local health departments, city governments, and community members and advocates must do to make health and equity a reality.

Coalition News

Webinar series returns with more inspiration for advancing public health

Our webinar series provides examples of big cities acting on the Urban Health Agenda in innovative ways.

Preamble: Health is more than health care

The COVID-19 pandemic has made clear how important governmental agencies are in protecting and promoting the public’s health. Big city health departments distribute masks, set up testing sites, administer vaccines, and gather data that officials use to decide how best to limit the spread of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. But public health departments do much more than respond to pandemics; they also ensure our food and water are safe, regulate tobacco, reduce the harms that can come from substance misuse, provide vaccinations for dozens of communicable diseases, and much more.

Unfortunately, the pandemic, in parallel with the murder of George Floyd and a host of similar injustices, has highlighted a truth that public health workers have known for many decades: that there are huge inequities in the health and well-being of people, particularly in our nation’s big cities. The racial justice awakenings of 2020 and the scourge of COVID-19 itself have called greater attention to the ways that racism, poverty, and a lack of community power harm Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) and other communities that are marginalized.

People who run cities make choices every day that affect the health and well-being of their communities. These choices can either help or harm, promote safe and healthy habits or discourage them, ensure access to resources for health for all or just for a privileged few, and inspire with creative design or extend historical oppression and marginalization.

In short, health is not just health care. Health is more than what we typically think of as “health.” To truly achieve public health, we also need full employment and a livable wage; safe, affordable housing; access to healthy food; well-functioning public transportation; safe, appropriate K–12 education; and access to routine and preventive health services. A truly healthy city requires a fuller commitment to health, defined broadly.

Health is not created within the health sector. Health is impacted by the conditions of people’s lives.

—Camara Jones, MD, MPH, PhD, epidemiologist, physician, and activist

Urban Health Agenda: Center health in all public decision making

Public health can and should sit at the center of decision-making processes across all city agencies. Although health departments play an important role in protecting and promoting the health of their communities, no single department alone can improve urban health.

To be successful, these efforts require partnerships and collaborations with all local government agencies, elected and appointed officials, and community-based organizations. The actions of every department in the city contribute to urban health, and each department has a critical role to play in doing so.

VIDEO: How DC Health and DC Water have worked together to address lead exposure inequities in their city

BCHC’s Urban Health Agenda advances health for current and future generations through big city innovation and leadership. The agenda highlights four key dimensions:

There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle, because we do not live single-issue lives.

—Audre Lorde, writer, poet, and civil rights activist

How we got here: Root causes of inequity

We must address inequity if we are to improve urban health overall. The health of everyone in a community is threatened when people in neighborhoods within the same city have life expectancies that differ by decades.

Inequity is primarily driven by racism, sexism, and classism. Each of these has contributed to systemic oppression in terms of laws, practices, and other norms that lead to negative outcomes. For example, owning a home is one of the best ways to build wealth in the United States, but people of color have traditionally been shut out by racist policies such as redlining, which excluded Black people from homeownership. This is one reason for the racial wealth gap.

Economic opportunities and a quality education are out of reach for too many people. This situation perpetuates fundamental barriers and widens the gaps in wealth and health. Political power is also not equally distributed, and communities without political power may struggle to be justly served by government and other institutions. Barriers to voting can make things even worse.

Where health comes from: Social determinants of health

Every aspect of our lives affects our health. To be healthy, we need reliable access to income, housing, fresh foods, transportation, education, and more.

Economic stability, which requires living wages and access to capital and educational opportunity, affects current and potential income. Income and stable employment also determine access to quality health care. Food security, safe and affordable housing, and educational opportunity all reduce stress, and reducing stress can also reduce risk for chronic disease and substance use disorders.

VIDEO: How Maricopa County uses community feedback and stories to shape future programs and services

The design of a city powerfully shapes public health. Studies show that, to be healthy, people need safe and affordable housing, level sidewalks with curb cuts to promote walkability, and green spaces to exercise and socialize, including parks. Trees, for example, lower temperatures, reduce stress, and improve overall health. People also need access to modern and well-resourced public health and health care systems to maintain their health.

Social context and community connectedness also influence our health. When they have social supports, people make healthier decisions and feel confident that they can find the right help when they need it. Health outcomes are also better in communities where people can find meaning and connection in religious and community organizations and where access to elections and civic engagement is unobstructed.

What healthy communities look like: Health and quality-of-life outcomes

Being healthy both physically and mentally means being free of injury and illness and being able to cope with the stresses of everyday life or emergent issues. Stress, especially chronic stress, has detrimental effects on the human body.

Research shows that people who endure difficult life circumstances, live in a dangerous environment, or experience racism are more likely to suffer physical and mental illnesses than those who don’t.

VIDEO: How Multnomah County collaborates with Black-owned farms to address food access and affordability

Thankfully, we know what a healthy city looks like: plenty of jobs with living wages for its people, walkable streets that promote connectedness, solid infrastructure, and reliable emergency services that protect the health and safety of residents. We just need to find the resources to achieve this vision in all communities, starting with the ones that have been most underserved and under-resourced.

Indicators of community health include high school and college graduation rates, as well as access to affordable fresh food, public transportation, and other important goods and services. In a healthy city, people know each other, participate in civic and community life, and are not routinely exposed to violence.

How we start to achieve equity

Structural tools

Governments have a variety of levers they can pull to address the root causes of inequity, alter the social determinants of health, and improve health and quality-of-life outcomes. Government can also use its power to set us back on this journey, and all too often this happens in communities that are marginalized or have been consistently left behind. Structural levers for change are most successful when government works with the community to make shared decisions and build collective power.

Like anything influenced by systems of power, these tools are not neutral. Only an intentional and sustained focus on equity will ensure that these tools generate positive systemic change instead of further injustice.

Critical structural tools include:

Laws and public policy. Laws are the ways that government codifies policies. All laws are policies, but not all policies are laws.

Organizational policies. An organizational policy is a written statement by a public agency or organization outlining their position, decision, or course of action.

Practices. A practice is a procedure that is customarily or habitually implemented by members of a profession.

Budgets. A budget is a plan for managing and allocating money—and it is a policy statement of a government’s aims. It is the primary way that governments select among competing demands for resources.

Collaborative governance. In this kind of governance, government agencies work with residents in the community to make policy and resource decisions.

Data and research. Research creates new knowledge and uses existing knowledge to generate new ideas and understanding. Research and data can illuminate the root causes of issues, highlight obstacles, and more.

VIDEO: How and why Columbus passed flavored tobacco restrictions in a politically diverse state

Governments must also dismantle the structural barriers that have hamstrung the work of public health. Dedicating appropriate resources and stopping preemption (in which state and federal governments prevent local governments from passing their own regulations) are just two ways that governments can dismantle structural barriers to public health.

Leadership roles

Big city public health departments know that health is complex and understand the many interconnected aspects of health. Health departments can lead in several key ways, including:

- Setting the agenda. Health departments convene community stakeholders and residents to gather authentic and critical input. These departments collaborate with the community and their colleagues across city agencies to set priorities that contribute to the public’s health. The public health workforce uses data, coupled with historical context and current events, to inform their work.

- Framing the narrative. Health departments can not only explain how government has contributed to the marginalization of many groups but also identify ways to move toward justice and equity. They are well versed in speaking truth to power—and the public—about routine and emergent health threats. They know how to build support for needed policy change, in part by using data to convey stories about the health of communities. And they understand and work to address actions that drive inequitable outcomes.

- Partnering across government and community organizations. Health departments thrive on community partnerships and outreach. They use government resources to create strategic opportunities for community members to share their knowledge and expertise. Health leaders can also help bring this approach to other city agencies.

- Using data to drive policy and practice. Health departments strive to have accurate, timely data on which to base decisions— although work is still needed to achieve this ideal. They routinely monitor health trends and communicate both short-term progress and longer-term impacts to their government colleagues and community members. Community voices provide context for the numbers, and the public health workforce translates data into action to share insights in an accessible and transparent manner.

VIDEO: Southern Nevada Health District and Seattle/King County explain how best to implement public health vending machines

The agenda in action: Cities as incubators

Here are some ways health departments have already been working with other stakeholders to improve cities in recent years. These tactics are a promising start toward a future where public health plays a role in all major urban planning.

Houston

Beginning in February 2020, the city health department did pioneering work with academic researchers to find a way to detect the virus that causes COVID-19 in wastewater. The department determined in which zip codes they should target public health efforts (vaccines, testing, etc.) and shared data with health care systems. The team is also looking into monitoring wastewater for influenza and other diseases. Explore Houston’s wastewater monitoring dashboard.

Phoenix

Maricopa County’s health department partners with faith-based institutions to provide vaccines for COVID-19, hepatitis A and B, and other diseases. For example, the department has worked with a Hispanic/Latino church to vaccinate asylum seekers. Watch the video.

Los Angeles

The Los Angeles County Department of Public Health partnered with Cedars-Sinai Medical Center to bring blood pressure treatment directly to Black barbershops, which are important community gathering places. Read the LA barbershop story.

Chicago

With funding from a foundation, the Chicago Department of Public Health mapped which parts of the city did and did not have ample tree cover and linked that map to social determinants of health. A total of 15,000 trees are being planted in parts of the city that need them most. Watch the video.

New York

The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene has opened overdose prevention centers for intravenous drug users and connects those who test positive for HIV and hepatitis with doctors. The department also assists in locating housing if needed. These measures help prevent overdose deaths and keep neighborhoods safer. Read the article.

Coalition News

Webinar series returns with more inspiration for advancing public health

Our webinar series provides further examples of big cities acting on the Urban Health Agenda in innovative ways.

This work has been made possible through the generous support of our many funding partners, including CDC Foundation, de Beaumont Foundation, Kellogg Foundation, Kresge Foundation, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.