Coalition OMB FY2023 CDC Funding Request

October 2021

October 12, 2021

The Honorable Shalanda Young

Acting Director

Office of Management and Budget

725 17th Street NW

Washington, DC 20503

Dear Acting Director Young:

On behalf of the Big Cities Health Coalition (BCHC), I write to ask you to provide the highest possible funding for the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), central to protecting the public’s health, in the President’s Fiscal Year 2023 budget. BCHC is comprised of health officials leading 30 of the nation’s largest metropolitan health departments, who together serve more than 62 million (or one-in five) Americans. Our members work each day to keep their communities as healthy and safe as possible.

We thank you for your continued leadership and support for our nation’s public health workforce and systems during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. As you recognize, federal funding for CDC and the programs that support local and state public health departments have remained largely stagnant for the past decade with the exception of supplemental funding provided over the past two years. Additional, sustained investments through annual funding is necessary to build back public health capacity for the next pandemic, as well as ongoing health challenges, like substance use disorder and chronic disease.

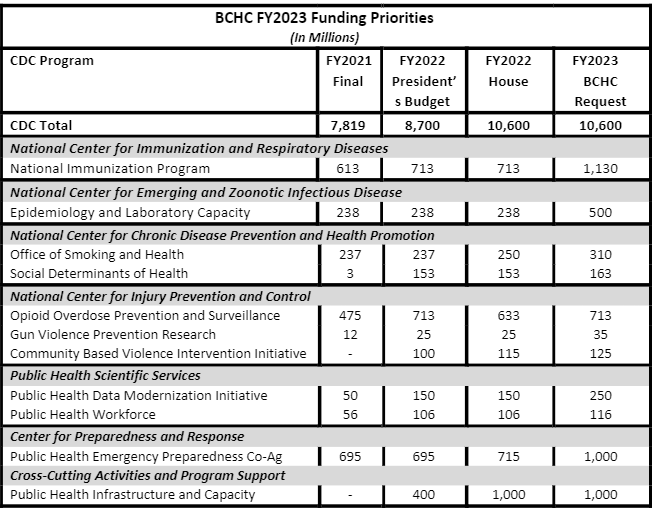

BCHC respectfully requests that you consider increases to the CDC programs listed below as you develop the FY2023 budget.

National Immunization Program

The CDC Immunization Program directly funds 50 states, six large, BCHC member cities (Chicago, Houston, New York City, Philadelphia, San Antonio, and Washington, D.C.), and eight territories for vaccine purchase and immunization program operations. In addition to the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic and continuing disease outbreaks, recent growth of electronic health records and compliance with associated regulations, new vaccines and school requirements have increased the complexity of vaccine management. Additional base funding is needed for each grantee to sustain improvements supported by emergency funding and maintain sound and efficient immunization infrastructure.

Epidemiology and Lab Capacity

The Epidemiology and Lab Capacity (ELC) grant program is a single vehicle for multiple programmatic initiatives that go to 50 state health departments, six large, BCHC member cities (Chicago, Houston, Los Angeles County, New York City, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C.), Puerto Rico, and the Republic of Palau. ELC grants strengthen local and state capacity to contain infectious disease threats by detecting, tracking and responding in a timely manner, as well as maintaining core capacity as the nation’s public health eyes and ears on the ground. While large sums of emergency funding have flowed through the ELC program, there is still a need for increased baseline funding to help build the epi workforce, enabling state and local health departments to begin to move towards establishing a minimum epidemiology workforce; to promote and offer training for state and local epidemiologists; and to monitor needs in state- and/or local based epidemiology capacity.

Opioid Overdose Prevention and Surveillance

Many health departments were forced to curtail opioid and other substance use disorder prevention and related services during the pandemic. Unfortunately, overdose numbers have increased in many communities, erasing progress of recent years. Previously, programs that connected with people in hospital emergency departments after an overdose had seen successful outcomes in steering people toward syringe services programs and treatment programs. However, these programs rely on in person interactions that have been scaled back during the pandemic. Funding is needed in local communities to ensure that substance use disorder prevention continues to stem the tide of overdose and death.

Gun Violence Prevention Research

Firearm violence is a public health crisis in the United States that impacts the health and safety of all Americans. Despite initial funding in FY2021 to research key issues around firearm violence, significant gaps remain in our knowledge about the problem and ways to prevent it; we need to continue and expand the research. Addressing these gaps is an important step toward keeping individuals, families, schools, and communities safe from firearm violence and its consequences. The public health approach to violence prevention includes working to define the problem, identifying risk and protective factors, developing and testing prevention strategies, and then, assuring widespread adoption of effective, targeted programs. Additional funds could provide grants to conduct research into the root causes and prevention of gun violence focusing on those questions with the greatest potential for public health impact. The goal of this research is to stem the continued rise of firearm violence across the country to make our communities safer.

Community Based Violence Intervention Initiative

The President’s FY2022 budget request included funding for a new Community Violence Intervention initiative to implement evidence-based community violence interventions locally. BCHC whole-heartedly supports such an investment and urges sustained funding over time to maintain programs. Violence, like many public health challenges, is preventable. Yet, the majority of public investments are used to address the aftermath of violence, too often through systems that can cause further harm. Communities can be made safer when we understand the events that have led to present conditions and act on this knowledge by implementing policies and practices that address the root causes of violence. By making investments in public health strategies within communities that are most impacted by violence, cities can work across sectors to shift from an overreliance on the criminal justice system and move from reimagining to realizing community safety.

Data Modernization Initiative (DMI)

The DMI is working to create modern, interoperable, and real-time public health data and surveillance systems at the state, local, tribal, and territorial levels. These efforts will ensure our public health officials on the ground are prepared to address any emerging threat to public health—whether it be COVID-19, measles, a foodborne outbreak like E. coli, or another crisis. COVID-19 exposed the gaps in our public health data systems and since then Congress has provided funding for DMI through the CARES Act and American Rescue Plan Act. These investments have been critical, but the public health surveillance systems must live beyond COVID-19 and be ready for any and all future threats. This requires long-term, sustained investment to not just build capacity at the federal and state level, but also at in cities and counties across the country.

Public Health Workforce

The public health workforce is the backbone of our nation’s governmental public health system at the city, county, state, and tribal levels. Investments must be made to build back the workforce, as well as attract and retain diverse candidates with varied skill sets. BCHC values CDC’s fellowship and training programs such as the Public Health Associate Program and the Epidemic Intelligence Service that extend the capacity of health departments and partners at all levels of government. CDC is now supporting EIS officers in big cities; we urge this to continue as additional funding is available.

Public Health Emergency Preparedness Cooperative Agreements

With the exception of supplemental emergency funding during COVID, the Public Health Emergency Preparedness (PHEP) grant to state and local health departments program provides funding to strengthen local (Chicago, Los Angeles County, New York City, and Washington, D.C.) and state public health departments’ capacity and capability to effectively respond to public health emergencies, including terrorist threats, infectious disease outbreaks, natural disasters, and biological, chemical, nuclear, and radiological emergencies. PHEP funding has been cut by over 30% in the last decade. The continuous barrage of wide-scale public health emergencies, the COVID-19 pandemic being just one, demonstrate the need to invest in these programs to rebuild and bolster our country’s public health preparedness and response capabilities. Our systems are stretched to the brink and will need increased and stable base funding for years to rebuild and improve. It is imperative these dollars reach the local level in those communities that are not directly funded.

Public Health Infrastructure and Capacity

The President’s FY2021 budget request included an important new investment in core public health infrastructure and support. The pandemic exposed the deadly consequences of chronic underfunding of basic public health capacity. Because public health is largely funded by disease or condition, there has been little investment in cross-cutting capabilities that are critical for effective public health. These capabilities include: public health assessment; preparedness and response; policy development and support; communications; community partnership development; organizational competencies; accountability; and equity. Governmental public health infrastructure requires sustained investments over time, and we believe this is an important start. An ongoing investment is critical to ensuring that our governmental public health system is prepared for the next pandemic as well as to strengthen the health of our communities every day.

Office of Smoking and Health (OSH)

Tobacco use has long been the leading preventable cause of death in the United States. Each year, it kills more than 480,000 Americans and is responsible for approximately $170 billion in health care costs. OSH has a vital role to play in addressing this serious public health problem. It provides grants to states and territories to support tobacco prevention and cessation, runs a highly successful national media campaign, conducts research and surveillance on tobacco use, and develops best practices for reducing it. Additional resources will allow OSH to address the alarmingly high rates of youth e-cigarette in addition to other forms of tobacco.

Social Determinants of Health (SDOH)

CDC’s SDOH program was initially funded in FY2021 to coordinate CDC’s activities and to begin to provide tools and resources to public health departments, academic institutions, and nonprofit organizations to address the social determinants of health in their communities. Local and state health and community agencies lack funding and tools to support these cross-sector efforts and are limited in doing so by disease specific federal funding. Given appropriate funding and technical assistance, more communities could engage in opportunities to address social determinants of health that contribute to high health care costs and preventable inequities in health outcomes.

Finally, it is important to note that beyond the handful of directly funded cities for certain programs (as outlined above), federal funding reflective of the burden of disease or the population served often does not make it to large urban health departments. CDC has recently made strides in broadening out those jurisdictions that are directly funded, for example, with the recent National Initiative to Address COVID19 Health Disparities Among Populations at High-Risk and Underserved, Including Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations and Rural Communities awards that went to 50 local jurisdictions (along with 57 states and territories). In addition, the CDC does not track how states are distributing federal funding locally so there is no way to assess the impact of federal dollars at the local level or lift up best practices of state-local funding arrangements. We urge OMB to continue to work with CDC to collect data on how funding is getting local and what methodology is used to determine the funding amount.

In closing, thank you for your continued support of governmental public health. As you craft the FY2023 President’s budget, we urge consideration of these funding recommendations for programs that are critical to the public’s health and safety. Please do not hesitate to contact me at 202-557-6507 or juliano@bigcitieshealth.org if we can be of further assistance.

Sincerely,

Chrissie Juliano, MPP

Executive Director

Big Cities Health Coalition