Frontline Blog

Impact of increasing heat waves on US cities: data analysis and environmental justice issues

August 2024

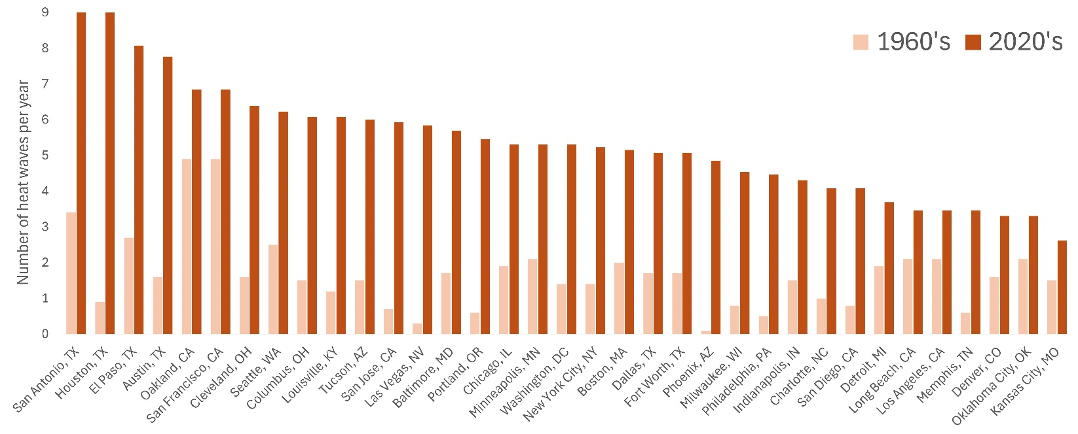

Already this summer, much of the U.S. has been under a health emergency due to dangerously high, record-breaking temperatures. Our new data shows that across big cities in the U.S., heat waves have increased threefold compared to decades ago.

In the past four years, large cities in the U.S. have experienced significantly more heat waves per year compared to the 1960s.

Heat waves – that is, unusually hot weather for at least two consecutive nights – are widely known to cause illness and death, particularly among seniors, people with chronic diseases, and those in lower-income housing.

As heat waves become more frequent, the summer hot season is also getting longer. Data indicates the season average is currently 30 days longer than it was decades ago. These conditions are already having profound wide-ranging impacts on our ecosystem and health; for example, longer pollen/allergen season, increased exposure to mosquito- and tick-borne diseases, and longer drought/wildfire season.

How extreme heat affects public health

Heat waves are just one among many threats to health from climate change. Climate-related disasters are federally declared and include severe storms, hurricanes, floods, wildfire, tornadoes, etc. A new metric on our data platform shows that climate-related disasters are already occurring every two years in BCHC cities and last for approximately 30 days. Disasters will become more frequent and devastating as warming oceans fuel extreme weather events. Hurricane season (June-November) 2024 is forecasted by NOAA National Weather Service to bring a record-number of severe storms and experts urge advance preparation to mitigate community impacts. Climate-related disasters can become humanitarian emergencies, destroying essential city infrastructure needed to maintain safe drinking water, sanitation and safety; they also can have long-term negative effects on health and wellbeing.

Get a guided tour of the data platform

As global temperatures increase, air pollution will likely worsen as hot and sunny skies increase ground-level ozone and wildfires become more common. In recent years, air quality degradation caused by massive, drought-fueled wildfires, industrial and auto emissions, allergens, and second-hand smoke has exposed millions of people to hazardous fine particles. These particles can cause lung dysfunction and lead to severe illness and premature death. The health effects of air pollution are most acute for young children, older adults, and those living with asthma and other respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. Metrics on our data platform indicate air pollution already significantly degrades air quality in BCHC cities for about 150 days per year.

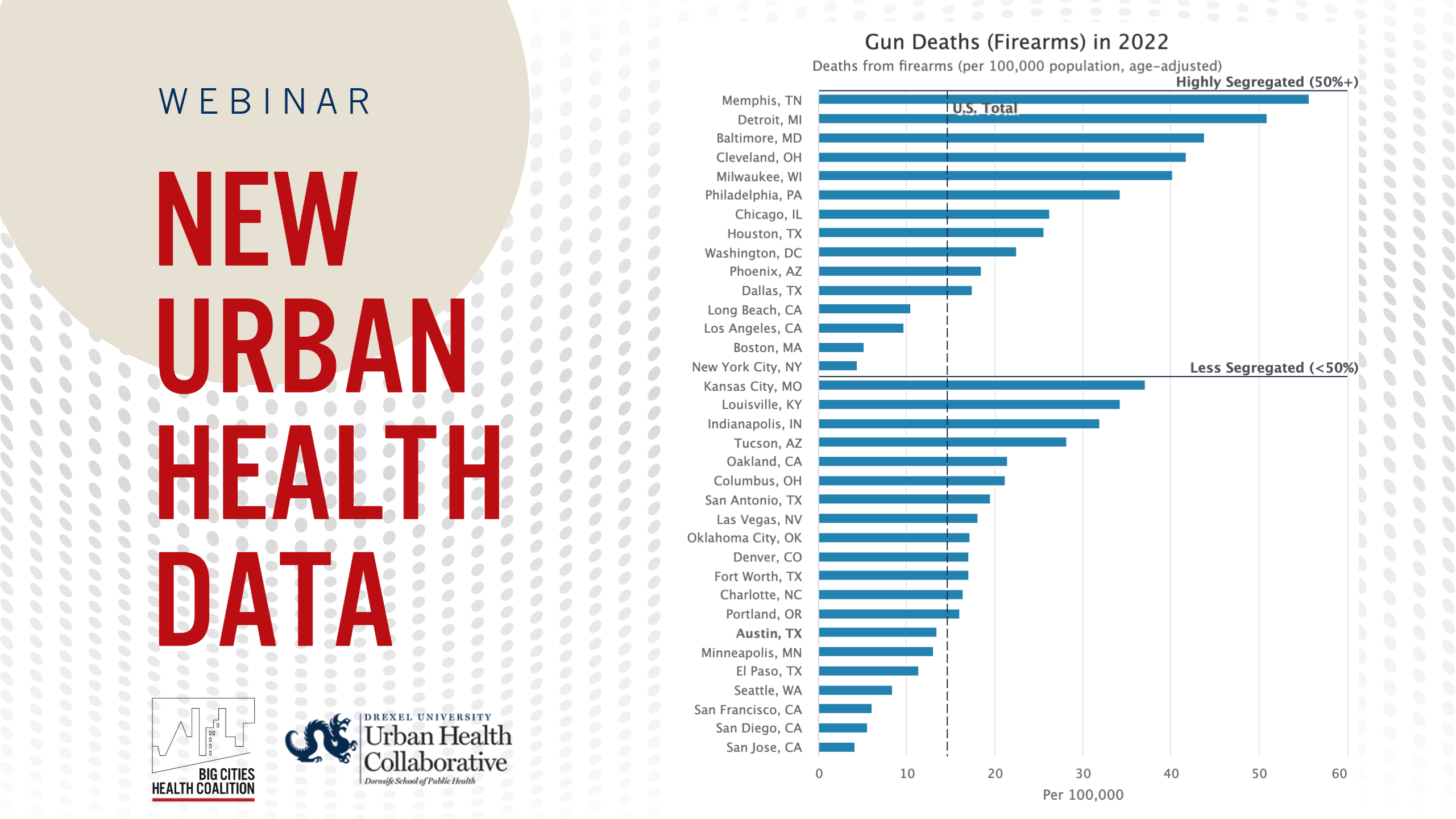

All cities have been impacted by the climate crisis, but the crisis has been particularly intense in cities that are already the hottest in the U.S. In BCHC cities in the southern and southwestern U.S. (especially Texas and Arizona), scorching temperatures last most of the summer: upwards of ninety days per year of daily maximum heat index ≥95°F. Compared to other BCHC cities, the hottest urban areas (such as Maricopa County) have already experienced a disproportionate number of heat waves, climate-related disasters, and worse air quality. Heat-related deaths have been increasing in the U.S. and we suspect that extreme heat is a factor in mortality rates in the hottest US cities, as well.

Environmental justice issues

The climate emergency we are experiencing is a human-made crisis that disproportionately impacts low-wealth and racially segregated communities. Long-standing structural inequities – including those created or perpetuated by federal and local policies – systematically exclude people living in poverty and communities of color from attaining financial security, economic mobility, and quality housing that could be protective against the effects of climate change and climate-related disasters.

While BCHC cities include high-wealth cities, on average BCHC cities have much higher poverty rates and are much more racially and ethnically diverse than the U.S. as a whole. A new metric on our data platform shows that on average, nearly 40% of city neighborhoods have high social vulnerability to climate disasters (compared to 25% for the U.S.) which places them at much higher risk of climate-related morbidity and mortality. Social vulnerability is determined by factors including socioeconomic status, racial residential segregation and other legacies of racial discrimination, home language, disability, and quality and safety of housing. Efforts in big cities to confront and prioritize challenges like poverty and income inequality, reinvestment in segregated neighborhoods, growth of migrant communities and availability of safe and affordable housing will build resilience to the negative impacts of climate change.

The way forward

Urgent investment in transformational change is needed to reduce health impacts from global heating by transitioning to a non-fossil fuel economy in ways that are socially equitable. Federal and local health officials are already partners in multi-sector climate action plans that aim to move cities toward this transition. At their best, these plans: prioritize decarbonization of the built environment while enhancing adaptation and preparedness systems in order to mitigate direct threats to health; include robust engagement of historically marginalized communities; and address upstream drivers of health such as equitable access to safe affordable housing and green jobs.

As we address climate change at national and global levels, big city health departments work to protect their communities’ health from extreme heat and other climate impacts. They not only educate the public about how to stay healthy in extreme heat, but also open cooling centers, provide free AC units to those who have none, offer financial assistance to community members who want to make their homes more energy efficient, and undertake tree planting projects to cool neighborhoods with little tree canopy.

Making improvements in the areas of climate change and environmental justice takes time and investment. Big city health departments are committed partners in that process.

These data are an example of new climate metrics posted on the Big Cities Health Inventory (BCHI) data platform. The platform is maintained by the Drexel Urban Health Collaborative (UHC) in partnership with BCHC and provides health metrics for the 35 large U.S. cities that make up BCHC.