Frontline Blog

Public health data modernization: moving from challenges to solutions

October 2024

Public health professionals need data so they can detect patterns and determine which solutions work best for their community. The COVID-19 pandemic illustrated the major gaps in our local public health infrastructure and how badly governmental public health needs resources to modernize systems for detection and response.

The need to modernize our data infrastructure continues, as we address ongoing challenges such as drug overdose, gun violence, disease outbreaks, and food-borne illness. In addition, our efforts to address health equity depend on having timely, accurate, and granular public health data, down to the local neighborhood level. Modernizing data systems will allow resources to get where they are most needed, ensuring everyone has their best chance at health.

We cannot afford to let our data defenses down when we aren’t facing an imminent disease threat. Historically, we have done just that, however – and have under-invested in public health, particularly at the local level. This has made the sharing, integration, and interpretation of data an overwhelming task and has contributed to inconsistent, incomplete, untimely, and less effective public health response.

Keeping our data infrastructure working for our communities means more than keeping our tech up to date. Equally important is the investment in a workforce capacity and capability to perform disease monitoring, data gathering, and reporting.

The modernization of data technology, systems, and workforce needs to happen at the local level. After all, it’s in local communities across the U.S. where front-line data collection happens at its most granular level. Local public health plays a critical role in using data to identify and strategically apply resources to those with the highest need. Local health departments also engage in the most direct service and immediate response to emergencies. Any data modernization effort must include significant resources to local jurisdictions.

Keeping our data infrastructure working for our communities means more than keeping our tech up to date. Equally important is the investment in workforce capacity and capability to perform disease monitoring, data gathering, and reporting.

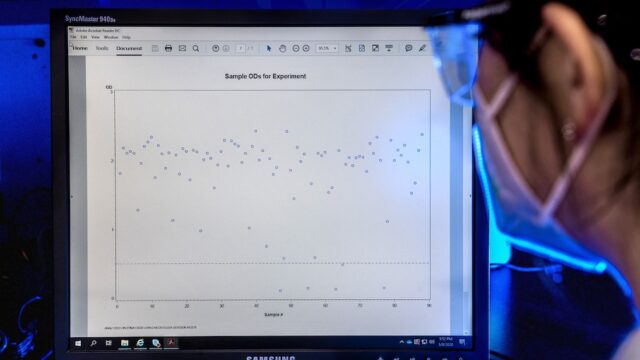

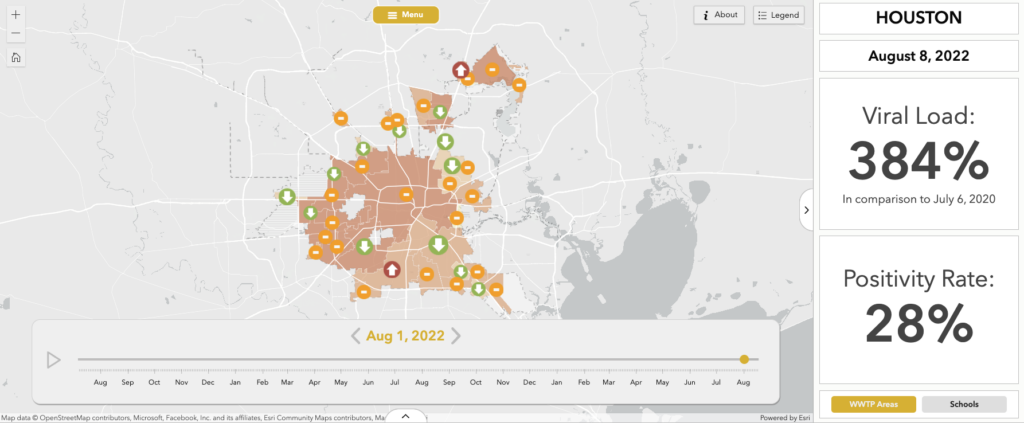

Big city health departments, in particular, serve as excellent laboratories for local data modernization efforts. They are often hit first and hardest by infectious disease outbreaks. And they push the cutting edge of data surveillance, as illustrated by:

In 2022, Houston Health Department became one of only two jurisdictions in the country to be recognized by CDC as a National Wastewater Surveillance System Center of Excellence.

Although our nation’s biggest cities serve populations that are even larger than some states’, most have not received any dedicated federal funding for data modernization. Without such funds, it is difficult to attract and maintain a capable data workforce and facilitate modernization and innovation. And without the commitment of future funding, sustaining any built infrastructure over time becomes impossible.

Identifying the challenges

In December 2023, BCHC surveyed its member data leads to understand what hinders data modernization within our largest metro areas. The figure below shows the challenges big city health departments face as they strive toward data modernization.

As the chart shows, resource and funding challenges rose to the top of their concerns, but respondents also pointed to other barriers to data modernization such as inadequate access to data and interoperability with state systems and health care providers.

From challenges to strategies

To better understand the investments needed to strengthen data modernization within our largest metro areas, BCHC partnered with CDC’s Office of Public Health Data, Surveillance, and Technology and the CDC Foundation to convene member jurisdictions in May 2024. The major themes and strategies are highlighted below.

1. Developing data governance

Gaps in current data governance structures have led to data gatekeeping and siloing. These silos occur both within and between local and state HDs, and health care systems. Without proper data governance, rights to access and share data are unclear, resulting in the lack of complete and accurate information that could be used to better serve communities.

2. Legal & regulatory environment

Jurisdictions highlighted the need to build partnerships between legal entities and public health agencies to shape policies and laws around public health data use and sharing both internally and externally.

One of this post’s co-authors, Dr. Phil Huang, discussing public health data modernization at the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists’ annual conference in 2024.

3. Developing the data infrastructure

Many public health data systems are siloed, not allowing the flow of information between program areas. Local jurisdictions must invest in the redesign of the data infrastructure and sustain this investment so it can grow to meet ongoing needs over time.

Jurisdictions highlighted the need for sustainable investments in more modern, interoperable systems. Some big city HDs have more sophisticated data systems than some states do, while others rely on outdated, legacy systems. A well-functioning data system requires investment to level-set across all localities and levels of government.

Respondents also emphasized the need for using modern, national standards for data collection and analysis, such as Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR), to improve interoperability and advance health equity.

4. Workforce: recruitment and retention

To build and sustain an agile data infrastructure that meets needs across public health sectors, a wide variety of specialized skill sets and roles are required. Jurisdictions report high turnover rates and employment gaps among public health informatics staff and leadership. In addition, local public health often struggles to attract and retain technology talent, as the private sector typically can offer more competitive salaries and benefits.

5. Workforce: training and in-house knowledge

Our members also highlighted that existing staff often lack the skills needed for informatics work, making training new staff and upskilling current staff important.

Data from the 2021 Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey (PH WINS) showed that 48% of big city health department staff plan to leave their jobs within a year or retire in five years. This attrition would leave a massive gap in institutional knowledge and workforce capacity and capability, along with subsequent costs of hiring and training new staff.

Investing in training and professional development will help mitigate these losses. Staff across multiple public health disciplines will need training on working with modernized data infrastructure. Once these systems are in place, staff must also receive ongoing training so they can strategically use data within their work.

6. Interoperability with state health departments and health care systems

In the survey of data leads, 96% of the jurisdictions reported being challenged by existing data exchange with their state health department. It is concerning that our nation’s largest metro areas struggle to secure a solid connection with state-level public health systems, even for data they originally provided to the state.

Big city health departments have reported similar challenges with obtaining data from health care systems. Integrating hospital data for both infectious and chronic diseases will be important to get timely information to identify the populations and hot spots needing resources and interventions. Support is needed to build stronger partnerships with state and health care partners to facilitate the flow of this critical information.

7. Limited resources

Based on the 2024 NACCHO Public Health Informatics Profile, although 94% of large local health departments surveyed are working on data modernization projects, only 29% receive any supplemental funding for this work.

For example, 90% of federal epidemiology and laboratory capacity (ELC) dollars go to states to support data modernization initiatives, and very little (if any) of the state funds trickle down to the local level. Because of the lack of investment, most big city health departments have to shift money from other under-funded areas to minimally cover critical baseline data needs, all while facing the fact that there are no guaranteed funding streams to sustain the necessary people, processes, and technology.

Conclusion

Our members are committed to ensuring the highest standard of health and wellness achievable for their communities. To do so, we need to do more to modernize and sustain the public health data infrastructure. Our efforts to address health equity depend on having timely, accurate, and granular public health data, down to the local neighborhood level. However, this cannot be accomplished through current practices and limited resources. To address the needs of our communities, local health departments need funding to perform work beyond the bare necessities, with direct and sustainable investments to enhance data modernization and the workforce to maintain it.