Frontline Blog

Big cities see slowing trend in drug overdose deaths: importance of harm reduction and addressing racial disparities

August 2024

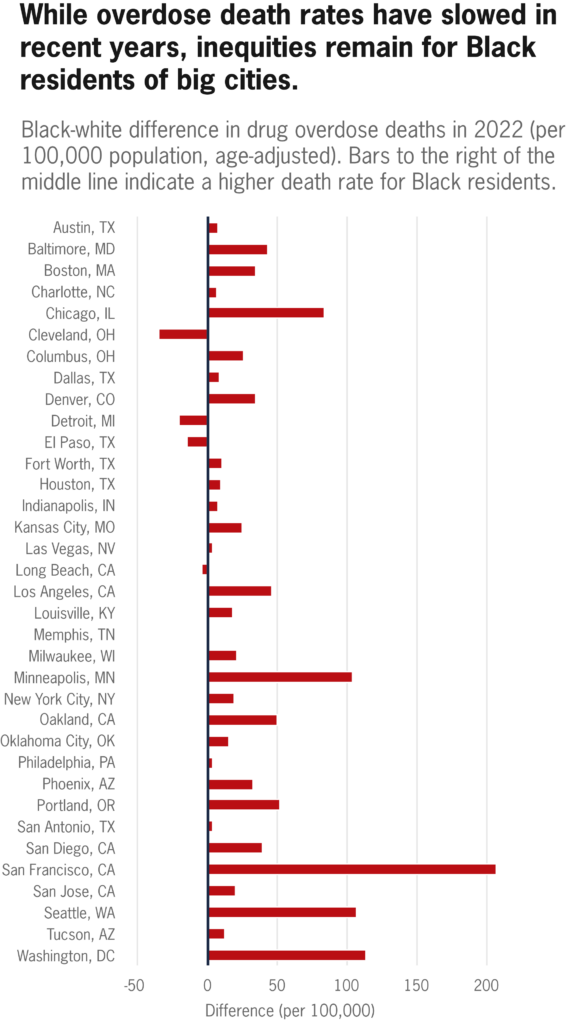

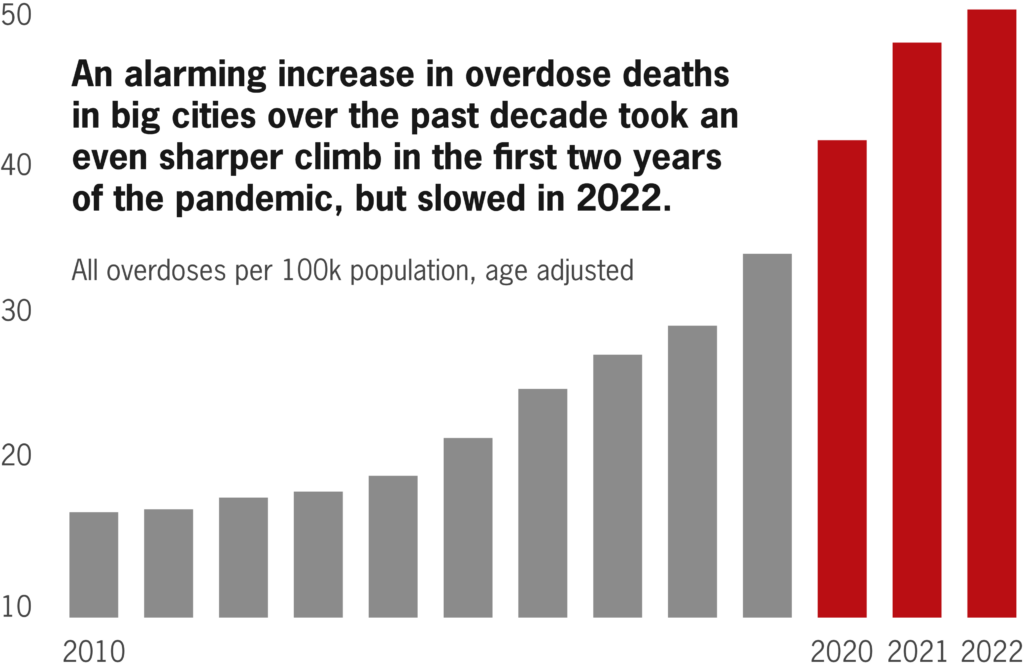

The most recent city-level data show that the alarming increases in drug overdose deaths from 2020 and 2021 have slowed and may be reversing. Big city health departments need stronger support to continue this positive trend by saving lives, addressing racial inequities, and bolstering our communities’ overall well-being and resilience.

The data show some encouraging signs that the overdose death trend may be reversing. In 2022, big cities saw a smaller increase in overdose deaths (as seen in the graph above), and in 2023 the U.S. as a whole experienced a decrease in overdose deaths. (City-level data for 2023 are not yet available.)

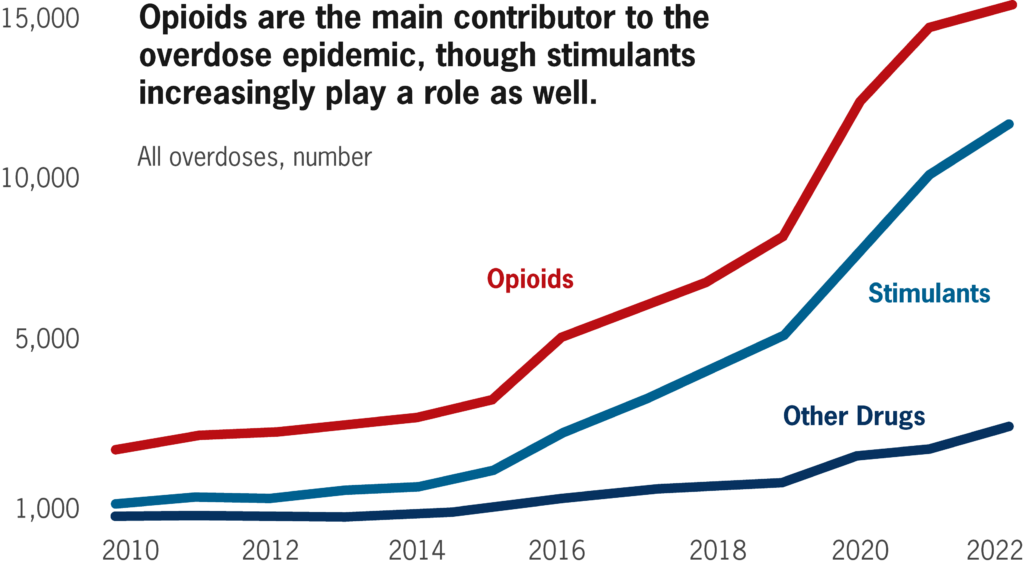

Big city health departments play an important role in responding to the overdose epidemic. The dramatic increase in the supply of fentanyl – a drug that is both inexpensive and can cause overdose even in minuscule amounts – has created a particularly challenging environment.

We are in a critical moment: more investment in evidence-based strategies for overdose prevention and harm reduction – and other supports such as low-barrier housing – could help keep the recent data trend moving in the right direction.

The right tools for the job: harm reduction

An important tool used by health departments is harm reduction, a set of practices shown to reduce harmful outcomes from substance use. As opposed to abstinence-only approaches, harm reduction meets people where they are, providing services and resources as a bridge to better wellbeing and connection to treatment options. Multiple studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of harm reduction strategies, including that they prevent deaths from overdoses, prevent transmission of infectious diseases, reduce emergency department visits and other costly health care services, and offer people who use drugs opportunities to connect to treatment and other health services in settings relatively free from stigma.

Among the 35 member cities within the Big Cities Health Coalition (BCHC), each employs a combination of public health strategies to best address substance use and overdose in their respective communities. For instance, the Southern Nevada Health District (which serves Las Vegas and the surrounding county) was one of the first jurisdictions to use vending machines to distribute harm reduction supplies such as naloxone, fentanyl test strips, and sexual health kits. Public Health–Seattle & King County recently launched a major social media campaign to educate youth and adults about fentanyl and reduce stigma. And several cities, including Columbus, OH, have established Mobile Crisis Response Units to send public health clinicians alongside police for calls involving a mental health or substance use crisis. Our recent polling found that city residents overwhelmingly support such public health strategies to address drug overdose and related issues.

Ongoing disparities rooted in systemic racism

In 2010, white Americans had the highest drug overdose death rate. A decade later, Black Americans had the highest rate. The rise in overdose deaths among Black persons is thought to be rooted in three interrelated factors:

1. Racism in health care – Black patients not prescribed opioids for similar levels of pain that white patients experienced

For similar levels of pain, Black patients have been prescribed opioids at much lower doses (or not at all). Lower opioid prescriptions to Black patients partially protected them during the early period of the opioid epidemic that was fueled by over-prescribing; however, it also contributed to Black persons being disproportionately reliant on street drug supplies.

2. Rapid rise in illicit synthetic street opioids (and mixtures of drugs) that are more lethal than heroin

In recent years, drugs that are more lethal than heroin – illicit synthetic opioids and mixtures of drugs – have dramatically increased the risk of fatal overdose among those disproportionately reliant on street drugs.

3. Systematically lower access to health care treatment options

Black drug users have systematically lower access to early intervention and health care treatment for addiction due to lower rates of employer-provided health insurance and wide variations in coverage whether by Medicaid or private insurance.

Federal policies needed to support local work

As big city health departments continue to address the overdose epidemic and work with their communities to create a healthy environment for everyone, specific policy changes at the federal level are needed to support their work:

About the data

To best implement public health tools like harm reduction, health departments require accurate and timely data. The Big Cities Health Inventory, an open-source platform providing health metrics for the cities that make up BCHC, allows health measures to be analyzed and compared across these localities. The Big Cities Health Coalition manages the platform in partnership with the Urban Health Collaborative at the Dornsife School of Public Health, Drexel University.

The Big Cities Health Inventory data platform is primarily funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through a cooperative agreement with the National Association of County and City Health Officials. The views expressed on the data platform do not necessarily represent the views of the funders.