Press Release

New report: Shortfall of big city health detectives poses serious threat to public health response

December 2024

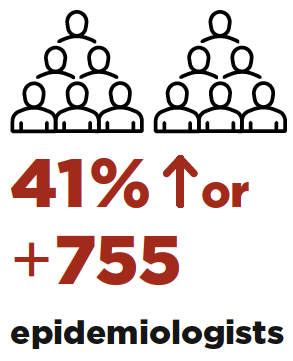

New (2024) study of big city health departments shows they are in dire need of epidemiologists. The shortfall puts at risk the nation’s efforts to quickly detect and respond to health threats.

WASHINGTON, D.C. – The Big Cities Health Coalition (BCHC) and the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) recently assessed epidemiology capacity in 35 big city health departments and found that our nation’s largest urban areas do not have the number of injury and disease detectives needed to fully protect and promote the public’s health.

Epidemiologists (or “epis”) in BCHC member cities serve on the front lines of public health, protecting more than 61 million, or one in five, Americans. Epis use many types of data to understand who gets what diseases or health conditions and determine why and how we can possibly prevent them. They investigate and respond to outbreaks and work to contain further spread.

Even at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, big city health departments did not have the funding they needed to hire the necessary complement of epidemiologists. As emergency dollars end or are rescinded, the shortfall of these public health data experts threatens to grow even further.

Epis are data specialists trained in statistics, computer science, and public health. Current funding allocations for ELC and other epi funding streams at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) make it very challenging for local health departments to attract and retain the highly skilled people in this field.

Big city health departments rely in part on federal funding from CDC to support positions in epidemiology, through its Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity (ELC) program and its various disease and injury divisions. Even at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, big city health departments did not have the funding needed to hire a full complement of epidemiologists.

As emergency dollars end or are rescinded, the shortfall of these data experts threatens to grow. With the end of pandemic funding, big city health departments anticipate losing 440 epidemiologists, or 24% of the workforce.

2024 Epidemiology Capacity Assessment

Get the full report 2024 Epidemiology Capacity Assessment2024 ECA Factsheet

Get the brief 2024 ECA FactsheetKey Findings

1. The need is urgent.

To reach full capacity, big city health departments need

Infectious disease epidemiologist, Columbus Public Health

Tell us a little about the work you do as an epidemiologist.

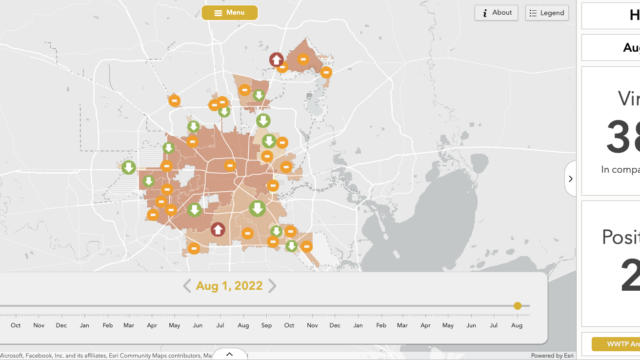

I am an epidemiologist at Columbus Public Health. I mostly focus on infectious disease, but I work in other areas as needed. For example, right now I’m working on our city’s Healthy Children and Safe Homes by 2040 initiative. We’re mapping out the data we have on how many kids have lead poisoning so we can figure out what areas of the city most need intervention and support.

How did you first learn about epidemiology and what drew you to it?

I got sick a lot as a kid – nothing too serious, but I did get scarlet fever and Lyme disease. While I was home sick from school, I loved reading about infectious disease because it helped me understand what was happening to me. I wanted to know the worst-case scenario. It didn’t scare me; it helped me understand. My favorite was Laurie Garrett’s 700-plus-page book, The Coming Plague – I read it when I was 11 or 12 years old. I didn’t know what an epi was at the time.

As a kid, I didn’t know what an epi was, but my first year of college I took a seminar with medical historian Howard Markel and I was hooked. My mom read his book, too, and she told me “you want to be an epidemiologist.” It took me a little longer to realize how right she was.

What has been the most exciting or impactful moment in your work?

I’m really proud of the work we did at Columbus Public Health to stem a measles outbreak in 2022. One of our infectious disease investigators told us about a couple of suspected measles cases in early November of that year. That part was not unusual – measles cases do crop up occasionally. But in the next few days, more cases appeared.

This is where the epidemiological investigation work began. We needed to trace who each child suspected of having measles had come in contact with. Many of the suspected cases tied back to one daycare center, and some of the kids who went to that daycare had also visited urgent care centers while they were contagious but not yet diagnosed. Our infectious disease investigation team kept doing interviews and found a lot more cases through these urgent care centers.

About a week in, the number of contacts we needed to interview had mushroomed. Even though we had created an incident command structure – that’s where people at the health department get called in to work on an emergency situation even if they don’t normally work in that area – keeping up with all the contacts grew very rapidly, so we requested an epi aid from CDC. Altogether our team called hundreds of parents and guardians of kids who may have been exposed. In the two weeks they spent with us, the CDC epi aid helped us prioritize which calls to make first, and when it was best to call people, and helped us inform local clinicians about how to recognize the signs of measles. We also got all our contacts into a system so we could automatically email them to ask if they were having symptoms.

While all this was going on, we also wanted to inform the larger community about what was happening, so my epi colleagues and I created a public-facing dashboard in Tableau in one day. The dashboard ended up appearing in the Washington Post and several other news outlets. It’s pretty rare that my work ends up in a newspaper.

Our last measles case that year got sick at the end of December. I’m proud of our department for its work to contain the outbreak so quickly.

Why do you think your work is important to your community (even if they don’t know it)?

A lot of decisions about health policy and practice get made based on epidemiological data. For example, in Columbus’ Lead 2040 initiative, we know we want kids to not be poisoned by lead. To get there, we need to know how many kids are currently poisoned, where they live, and where lead service lines still exist. (We work with the city’s Department of Public Utilities on that last part).

Epis collect and organize data about our communities so we can make more informed decisions about how to protect everyone’s health better. The data help us find those redlined neighborhoods and other areas that most need investment and support.

2. Federal funding priorities and shortfalls have led to insufficient focus on critical health issues beyond infectious disease.

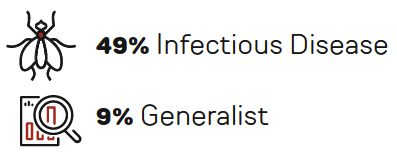

In 2020, big city health departments shifted many of their epidemiologists to focus on COVID-19 and other infectious diseases. Our cities lack sufficient staff needed to address these areas and are even more short-staffed to address pressing issues such as drug overdose and violence.

Nearly half of the epidemiologists at big city health departments focus on infectious disease

Program areas supported by the fewest epidemiologists are wastewater surveillance (19), genomics/Advanced Molecular Detection (16), violence prevention (15), injury (14), reproductive health (4) and oral health (3), which together accounted for only 4% of the total.

The paucity of injury and violence prevention epidemiologists is especially striking, as unintentional injury is the third leading cause of death in the United States.

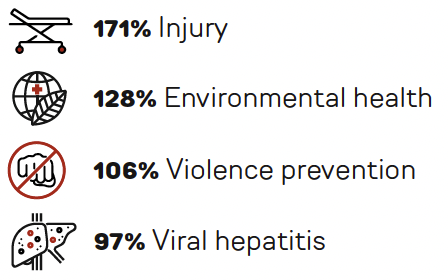

Big city health departments have the greatest unmet need for epidemiologists in these areas*

* Numbers indicate percent increase needed to reach ideal number of epidemiologists in that area.

Communicable disease epidemiologist, Public Health–Seattle & King County

Tell us a little about the work you do as an epidemiologist.

I’m in our Communicable Disease Epidemiology & Immunization Section in our Analytics & Informatics Branch, where I focus on respiratory viruses. We get data from lots of different sources, such as hospitals, lab tests, and wastewater. Clinicians usually look at an individual’s data to help them assess the health of their patient; as epidemiologists, we look at all this data to assess the health of our community. So, a big part of my job is doing the technical work needed to make that data ready for analysis so we can use them to figure out the larger trends. I help create our public dashboards, which are graphs we constantly update so residents of our county can see what’s happening with infectious diseases locally and in real time.

How did you first learn about epidemiology and what drew you to it?

In college, I started out studying philosophy and economics. I was really interested in development economics because I wanted to help people at a bigger, systems level. I first learned about epidemiology from friends who worked in humanitarian aid. In particular, I heard that organizations like Doctors Without Borders had epidemiologists use data during the Ebola outbreak in 2014 to guide their interventions. So, I was drawn to epidemiology because I could still use the statistics and modeling skills I’d learned in economics to help people on a large scale.

What has been the most exciting or impactful moment in your work?

As part of my job, I put together in-depth reports with our team for our leadership so they can make data-informed decisions about how best to protect the city and county’s health. One of my favorite examples is how we worked with local hospital leaders and other counties to create policies based on data for when it’s time to mask up to protect themselves and their patients. The data and analysis we provide about COVID-19, influenza, and RSV gives our health care providers the information they need to decide when to mask and when not to.

It’s been exciting to see the impact of that work, not just in our county but across the state and country as well. We’ve been sharing our methods with other health jurisdictions – including in a journal publication and with our state health department in Washington – and it’s great to see the impact of our work ripple out.

Why do you think your work is important to your community (even if they don’t know it)?

In an emergency situation like COVID, our work has immediate impact. For example, we provided data to our leadership to help guide policy decisions, including pinpointing what areas could benefit the most from additional vaccination efforts. And we continue working outside of emergency situations to improve the health of our community. In King County, racism was declared a public health crisis, so we’re continually looking into the impact of respiratory viruses on different groups. In particular, we look for disproportionate impacts within the larger trends so these issues can be addressed.

What do you wish people understood about what you do?

I wish they understood that I’m not a dermatologist! It’s funny – people make that mistake a lot, but I’m an epidemiologist – I look at health trends, not rashes.

But seriously, I wish we had more conversations with the public about what we do. I like learning more about what people want to know about health in their community. I want to know what they think is useful, because the work I do is for them.

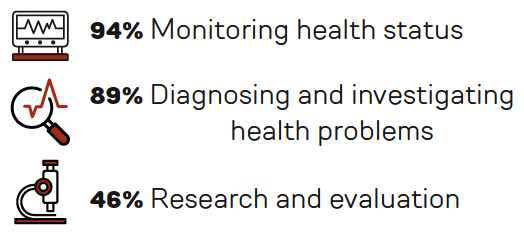

3. Big city health departments have high capacity for monitoring health status and investigating problems, but far less capacity for research and evaluation.

This gap leaves many local health departments with insufficient capacity to fully assess and improve upon outbreak responses and plan for the future.

Percentage of departments that report substantial to full capacity for conducting these activities

Binational/tribal epidemiologist, Pima County Health Department

Tell us a little about the work you do as an epidemiologist.

I am the binational/tribal epidemiologist for Pima County Health Department in Arizona. This means I work primarily with the tribes in and around Tucson. I oversee their cases, especially those that occur within the county but outside the reservations. I also share information with the tribes when they need it.

Another important part of my job is working with asylum seekers at the U.S./Mexico border. I screen people and if they have a communicable disease, I recommend treatment for them and get them to a hotel to stay isolated until they are no longer infectious; I also connect them with resources for any other immediate needs they might have like food or transportation. I keep the Pima County Health Department updated on what diseases we’re seeing so we can be prepared to protect the full community.

I’ve taken patients to clinics to be evaluated for different diseases. I stay in the exam room with the patient and a translator so we can facilitate communication between the patient and their clinicians.

For both parts of my job – working with tribes and asylum seekers – it’s very important that I understand customs, protocols, and expectations, so I spend a lot of time working to better my knowledge about these things. That mutual trust is so important.

How did you first learn about epidemiology and what drew you to it?

I was originally a cardiopulmonary technologist, so I had a lot of experience with health on the clinical side. I have also worked with STIs – that’s where I learned my interview skills.

I first studied public health at the University of London. I made the shift because I wanted to change my focus from clinical work to population health. I had no idea what I was getting myself into – the study of epidemiology can be very different from the day-to-day practice. I thought I would be sitting at my desk working through medical records, but for migrant and tribal populations there are very few records. That means I have to ask tons of questions and discover a lot on my own.

It’s challenging; there’s a lot to learn, and I encounter new situations every day. “The migrant population” comes from so many different countries, cultures, and languages.

What has been the most exciting or impactful moment in your work?

The faces of migrants when they realize that I’m there to help them, not to move them somewhere else. The realization they can relax for a moment. That moment keeps me going. Most of the migrants I see are walking from Ecuador to Tucson. They have been processed by border patrol, have answered a million questions, and have struggled with language barriers and mistrust.

I ask them what their final destination is, and I tell them how much I like that place and tell them more about it. We’ll sometimes talk about their skills and whether they can find work. I’m always trying to give them hope.

Why do you think your work is important to your community (even if they don’t know it)?

Epis work behind the scenes. The overall result of what I do keeps people and the community safer, including the people I work with. The people I work with are important to me. The community is important to me. I don’t need any recognition. It’s just satisfying to me take care of the people in my community.

What do you wish people understood about what you do?

I wish people understood the overall impact public health departments have on their well-being. We do so much behind the scenes to keep people in the county, the state, and the nation safe. Everyone is much better off because of us.

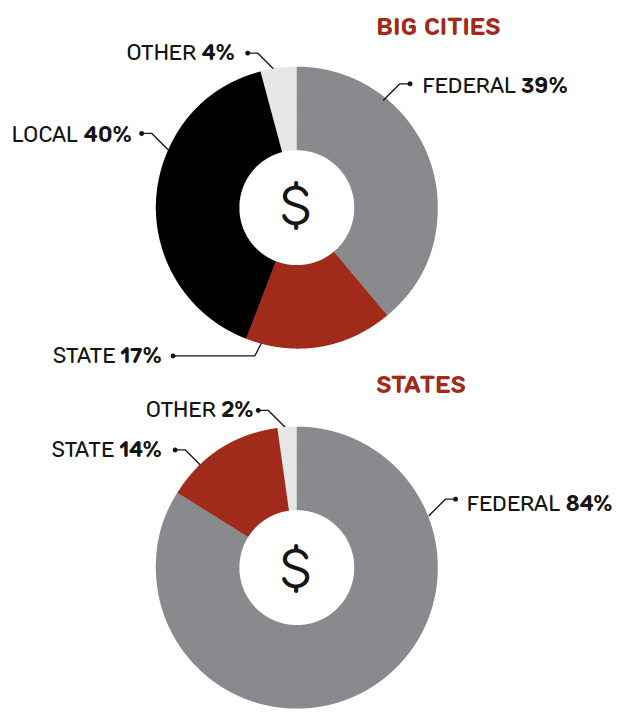

4. One reason for these gaps is that federal dollars to support epidemiology personnel largely go to state health departments. Little of this fundings gets to the local level.

Methods

With input from big city health department staff, CSTE and BCHC modified CSTE’s state epidemiology capacity assessment to better suit large, local health departments. All 35 BCHC members participated. Data collection occurred from March to June 2024. Quantitative data were analyzed using R Studio statistical software and Excel 2008 and qualitative data were coded and grouped thematically. Where relevant, data were compared with those from the 2024 state ECA.

2024 Epidemiology Capacity Assessment

Get the full report 2024 Epidemiology Capacity Assessment2024 ECA Factsheet

Get the brief 2024 ECA Factsheet